Several studies show that Gen Z demonstrates a high concern for sustainability, yet they happen to be the greatest consumers of fast fashion. Much of what we call self-expression is just algorithmic homogenization of the internet.

Though we may like to believe that we have jurisdiction over our ‘taste’ and ‘style,’ the algorithm might be more in control of it than we think. And as ironic as it is, for a generation so seemingly obsessed with proving one’s hyper-individuality, we do want an unreasonable amount of the same things.

What we often mistake for personal style is in fact the product of digital repetition and influence, revealing not only overconsumption, but also underlying confusion about identity, sustainability and self-expression.

How a trend comes to be is an intervention of multiple phenomena: it starts with an item, either aesthetic or gaining attention that tips off the algorithm. Engagement is prioritized over actual quality, and the same content is catapulted to everyone’s feed to multiply exposure.

Before we know it, we fall prey to the bandwagon effect, watching the same thing, over and over again, oftentimes confusing familiarity for interest. Skillful scarcity marketing creates an artificial sense of urgency and one is left to wonder what it is about the Pop Mart Labubus that sell out in seconds and how the life-sized versions of it are valued over $150,000 at auctions, higher than almost twice the average American’s annual income.

Surely one is allowed to agree with the perceived necessity of an item in their life, even if that opinion originates from something they saw online. This becomes a problem, however, when the entirety of the target audience wants the same things — and there are hundreds of such things to want.

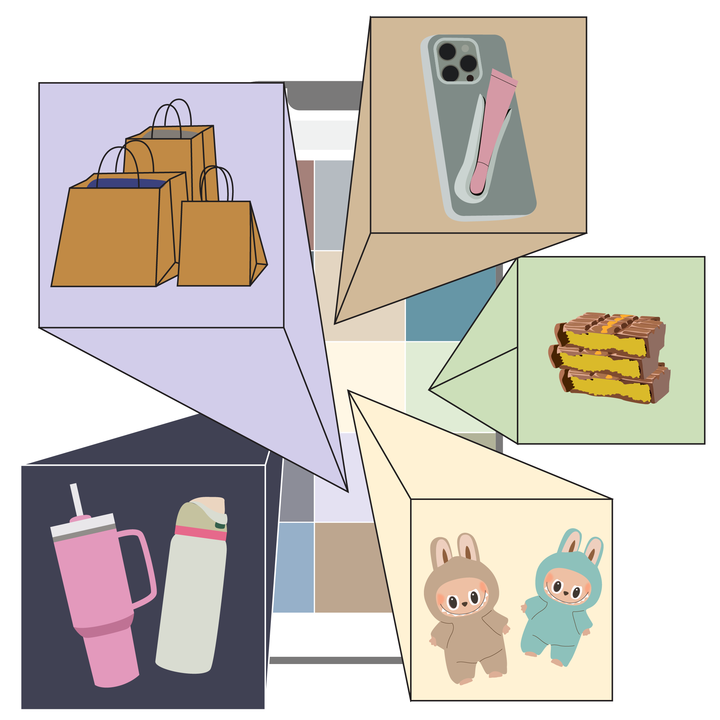

The Rhode phone case offers virtually no functionality — if anything, it was only harder to fit in your pocket or purse, yet its demand proved otherwise. Despite inflation, we find ourselves paying three times the price for chocolate strawberries just because they are the Dubai Pistachio Kunafa edition, something so demanded that it triggered a global pistachio shortage. To participate in something like the “clean girl” trend, it’s not enough to just wear yoga sets. It’s a lifestyle you must embody, incomplete without posting about an overpriced beverage and pilates class online. The object often has lesser value than the performance of its aesthetic, which reflects how repeated exposure can be mistaken for genuine interest.

And in chasing this performance, we begin to collect not things we necessarily love, but rather ones with the objective to signify belongingness to a trend. This is not self-expression, but rather unacknowledged overconsumption.

Thrifting, for instance, was once a well-intentioned effort towards affordability and sustainability. The secondhand apparel market saw an astronomical rise in recent years due to popularization online. The result? Bulk buying at thrifts, price markups by resellers and the quiet gentrification of spaces once meant for low-income communities. All the thrift hauls by influencers on YouTube still reinforces the desirability of having an endless closet, not the essence of sustainability through repurposing. Overconsumption is still overconsumption, regardless of whether it was done at a thrift store.

The most obvious consequence is ecological — every mass-produced item, shipped and soon discarded at its trend expiration date accelerates the fast fashion crisis, a system already responsible for about 10% of the global annual carbon footprint.

The toll lesser talked about, however, is emotional. Being unable to keep up with online trends establishes a cyclical relationship where peer-comparison leads to increased mindsets such as the fear of missing out, subsequently lowering self-esteem and heightens anxiety, a ResearchGate study finds. The loss of our individual uniqueness is another price we pay when the algorithm causes so much of our beliefs to become homogenized.

The objective is not to undermine the quality or subjective desirability of anything currently popular online, but rather to reflect on the unprecedented scale trend adoption has taken on in our generation and what it really says about our lack of self identity and personal opinion.

By being chronically online, it becomes increasingly harder to form opinions of our own that are authentic because of the thousands of curated visuals thrown at us. In psychology, this confusion between internal preference and external influence is tied to a concept called self-concept clarity — how clearly and confidently one understands who they are. This being especially weakened during youth, we begin to like things not because we truly appreciate them, but rather because they feel familiar, desirable and socially rewarded.

You cannot fast-track personal style. We are depriving ourselves of the journey it takes to discover what truly resonates with us. The truth is, something you genuinely like will never go out of style for you, and that is why so much focus needs to be laid on conscious consumption and purchasing pieces that stand the test of time. We owe it to our minds, our wallets and the sake of our planet to introspect — to live with fewer contradictions in our very existence and make mindful choices that reflect who we are.

Sara Khan is an Opinion Intern for the summer 2025 quarter. She can be reached at skhan7@uci.edu.

Edited by Rebecca Do, Annabelle Aguirre